Patching ELFs with Assembly C, or abusing the linker for fun and profit

Using a little bit of linkerscript magic and C to patch binaries the toolchain-intended way - instead of manually patching assembly instructions like a madman.

In this post, we’ll explore an intuitive way to patch program behaviour in ELF binaries - by using a method that involves NO assembly.

TL;DR#

Feel free to skip to Simple demonstration section if you are familiar with C compilation process and linkerscript.

Compiling C - a quick refresher#

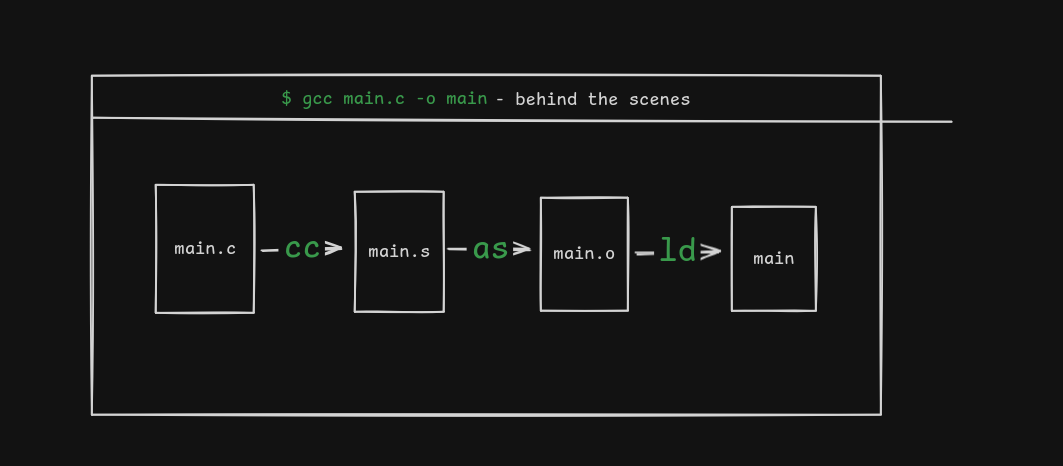

Compiling C, in the most simplest form, is as simle as a single command like gcc main.c -o main.

But behind the scenes, there’s three main components involved in converting a C source file to an executable - the compiler, the assembler, the linker.

Abusing the linker for fun and patching binaries#

In the compilation process, the linker is used to resolve relocations in object files.

The GNU Linker (ld) provides two features that can be used for binary patching:

- Defining the address of a symbol.

- Placing a certain section of code at a certain memory offset.

Defining the address of a symbol#

In C, symbols may be referenced before they are defined. This allows code to refer to objects or functions whose final definition is provided later-either by another object file or by the linker itself.

Symbols defined in linkerscript can be referenced using the extern C keyword (It’s not necessary for functions).

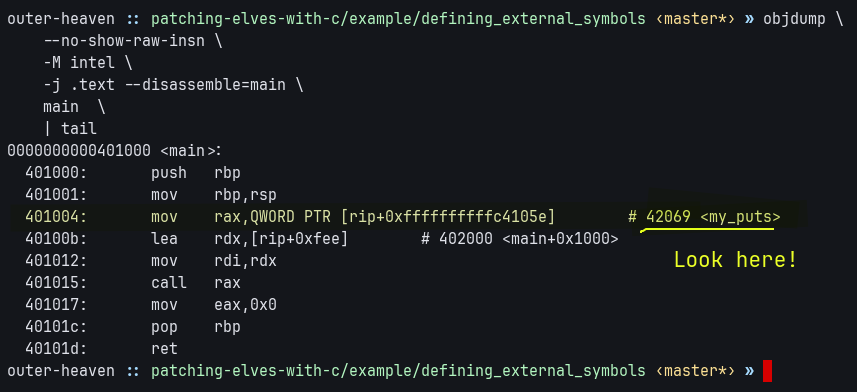

The below example shows a linkerscript which defines the address of the symbol my_puts to be 0x42069.

It can be verified by looking at corresponding disassembly.

C — MAIN.C

| |

LD — LINKERSCRIPT.LD

INCLUDE default.ld

my_puts = 0x42069;

Feel free to download and compile the contents of example/defining_external_symbols/export.zip to verify.

Placing a certain section of code at a certain memory offset#

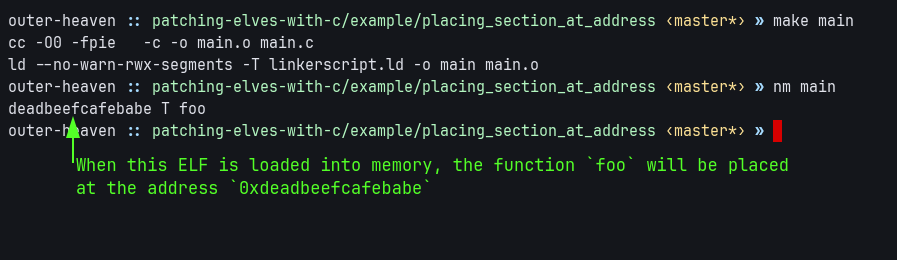

By modifying the location counter (the .) of a linkerscript, we can force certain sections to be placed in specific virtual addresses.

For example, the below code places the function foo at the virtual address 0xdeadbeefcafebabe.

C — PATCH.C

| |

LD — PATCH.LD

SECTIONS

{

. = 0xdeadbeefcafebabe;

.patch ALIGN(1) : SUBALIGN(1)

{

KEEP (*(.patch))

}

}

The source for this example is provided at: example/placing_section_at_address/export.zip.

Simple demonstration#

For a practical example, we will patch a binary produced by the following source:

C — PATCHME.C

| |

The goal is to replace the code-cave i_do_nothing with a call to

C

| |

without recompiling the original source.

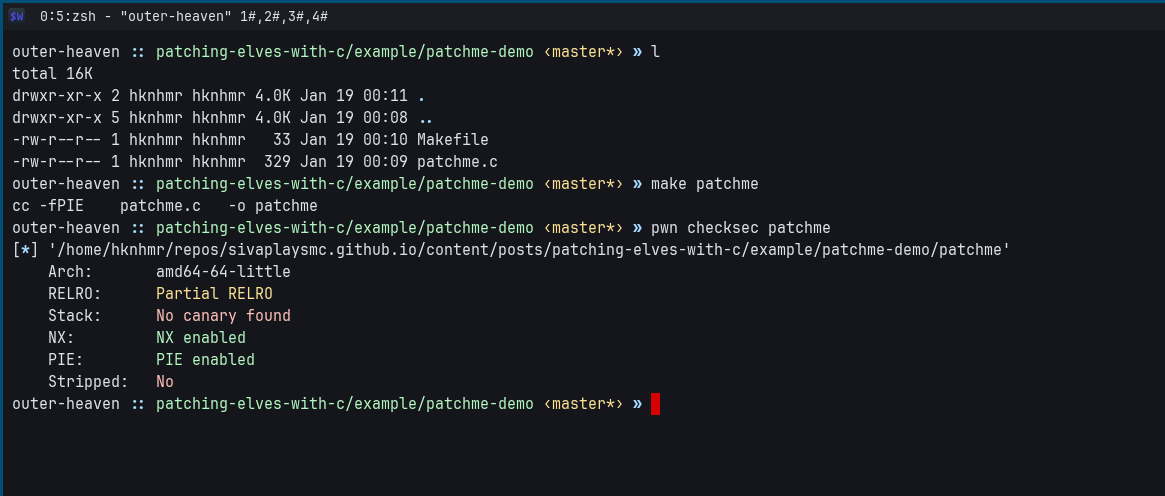

The binary has the following protections enabled:

The most notable one, for our concerns, is PIE (Position Independent Executable).

Since it is enabled, we cannot call to absolute addresses - we have to make the compiler emit the rel32 counterparts of the call / jmp instructions by setting a flag.

Notation#

Moving on, the word “target” refers to the binary being patched.

Recon#

Before we start writing the patch, we need to identify code caves and enumerate the environment.

We need a safe-to-patch code cave.#

When patching a code cave, it should not cause un-wanted side-effects (like triggering improper memory access).

The i_do_nothing function provides a perfect code cave, with 500 nop instructions.

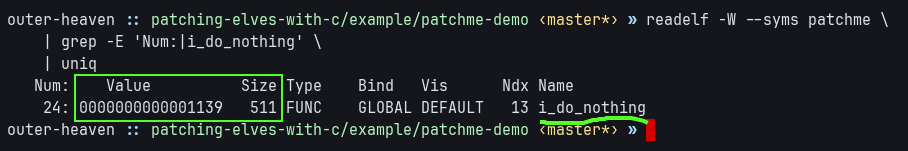

It starts at physical address 0x01139 and has a length of 511 bytes.

We need to call external library functions#

Our goal is to call puts.

Since the target is dynamically linked, we can find a reference to puts in the .plt section,

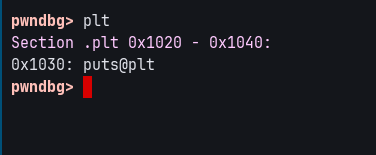

at the physical offset 0x1030.

Writing the patch#

From our recon, we have the following parameters:

- should fit within the address range

[0x1139, 0x1139+511]. - must call

puts, which can be achieved usingputs@plt. - must also embed two null-terminated strings (the parameters to

puts@plt).

With the above in mind, one can write a patch - something similar to this:

C — BINPATCH.C

| |

LD — BINPATCH.LD

patch_at = 0x01139;

patch_size = 511;

puts = 0x1030; /* plt entry of puts */

SECTIONS

{

. = patch_at;

.patch ALIGN(1) : SUBALIGN(1)

{

KEEP(*(.patch.code.*))

KEEP(*(.patch.data.*))

}

ASSERT(SIZEOF(.patch) <= patch_size, "patch is too big")

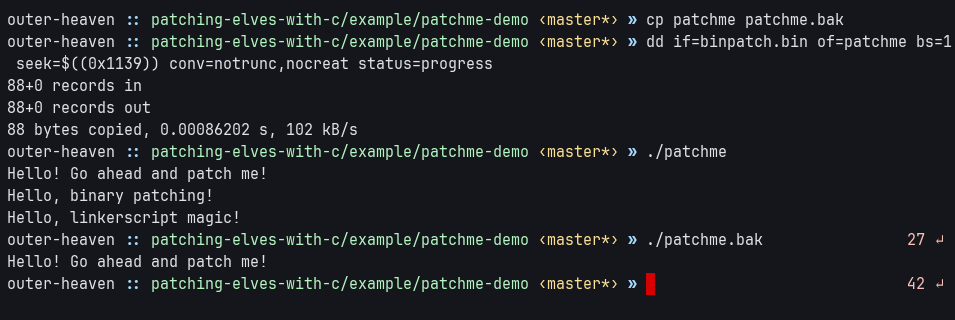

}Once the patch is compiled and extracted, it can be applied to the target using the dd command.

Caveats#

- If the codecave is restricted by size, it is a better idea to directly write assembly.

- If the target function’s calling convention differs from the C compiler’s ABI, it’s preferable to use a small assembly “stub” to adapt the arguments and invoke the C function correctly.

Conclusion#

The original goal of this method of binary patching was to increase productivity by working with a high level tool like the C compiler instead of an assembler. That said, it also comes with a few pretty useful side effects. I’ll revisit the points outlined below in more detail in future posts:

With enough compiler options, it should be possible to use languages other than C for generating object files. Example: Rust, Zig, Nim, etc.

The patch itself gains a degree of platform independence: as long as the target and the patching language share the same (or similar) ABI, the patch logic remains unchanged. The only platform-specific component is the linker script, which defines the required symbols, addresses, and offsets.

This method should work fairly unchanged for other binary formats, like PEs or Mach-O executables.

With a large enough code caves, it should be possible to embed a dynamic symbol-resolver, which uses platform dependent methods to load addresses of symbols from libraries (like

dlsym()on linux, andGetProcAddress()on NT).

Overall, this method shifts binary patching away from instruction-level edits to a more structured, maintainable and versionable workflow. It mirrors how decompilers let us think in C while reverse-engineering: the low-level complexity of assembly still exists, but the compiler handles it for us, allowing us to focus on intent rather than instructions.